Ever since I wrote for The New York Times about extra-long cakes, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the resurgence of surrealism.

In reporting for that story, I stumbled upon the rich world of large-format food and creative direction, which evoked images not too dissimilar to Salvador Dalí’s surrealist cookbook. After speaking with art historians at Oxford and University of Pennsylvania and then deep-diving into the work of Laila Gohar and Zélikha Dinga, I knew this was something I wanted to explore more.

Since the summer, my Instagram has been filled with enormous (apparently some CGI-generated?) luxury marketing activations by Jacquemus, Isabel Marant, and Netflix.

These are stunts to get attention, but that’s nothing new for surrealist art. According to The Guardian, “[Dalí] was the first celebrity modernist. Picasso and Matisse were famous – very famous – but the work came first, celebrity second. By contrast, when Dalí made a speech in a diving suit or collaborated with Alfred Hitchcock, he was turning self-promotion into an art form – setting the stage for all artists who have become pop culture icons.”

With that in mind, I sat down at my computer a few weeks ago to pen some thoughts on this question: Is everyone influenced by Salvador Dalí? Or, said differently: Why am I seeing eggs everywhere?

As I began to dig into several Dalínian symbols (eggs, lobsters, melting, large-format food, swans), it became clear that trying to answer my original question only birthed new ones. With the obvious and essential caveat that I’m not an art historian, I’m going to tell you why everything feels surreal.

What Do You Mean Surrealism Is Everywhere?

*Cracks fingers*

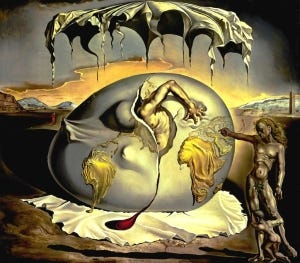

Eggs

What is the significance of eggs?

According to the Salvador Dalí Museum, eggs in Dalí’s work “symbolize birth, love, and hope. This symbol is very important because it also represents his wife Gala’s gaze and the resurrection of Christ.”

I spotted eggs in the viral Simone Rocha egg bag (do I need this for my wedding?), Sandy Liang by CENTÁ, the egg chandelier by Gohar World, the Loewe cracked egg heels, and the Lisa Says Gah egg earrings.

Lobsters

What do lobsters mean?

According to Tate,“Dalí often drew a close analogy between food and sex.” Furthermore, FormFluent noted that, “Being an aphrodisiac, lobster is often associated in art with eroticism and pleasure. Many people believe that Dali used the animals in his work because of these strong sexual connotations.” Vogue did a deep-dive titled “Lobsters in Fashion: A Timeline of Crustacean Chic” which does an amazing job of compiling contemporary lobster fashion references.

Elsa Schiaparelli and Dalí Lobster Dress: You could go on a deep-dive on the lobster dress alone, worn by Wallis Simpson (wife of Edward VIII who abdicated the throne) in a 8-page spread in Vogue in 1937. In 2012, Anna Wintour wore a Prada dress to the Met Gala that was made by Prada in homage to the iconic lobster dress.

Dalí’s Lobster telephones: One of the eleven Dalí that created for Edward James is housed in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. I ventured to the museum to see it and apparently it is on loan for the next year! Fun fact, a private buyer tried to buy the artwork and the UK government blocked its sale.

Large-Format Food

What’s the connection between large-format food and surrealism?

Large format dessert and food as art is absolutely having a moment. There are many artists using large format food as a medium, including Laila Gohar, Zélikha Dinga, Food Rituals, and more.

In one super fun event, fashion designer Blanca Miró had a surrealist birthday party, produced by Food Rituals.

As I reported for NYT about extra-long wedding cakes, desserts are getting longer and larger—brands Ganni and Ghia both recently had towers of croquembouche at their events.

Here are two fun further reads about the surrealist influence on food in Frieze and NYT.

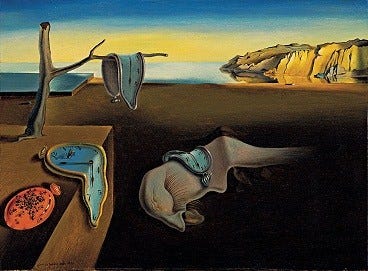

Melting

What does melting mean?

According to the Salvador Dalí Museum, “The melting clocks are symbols for the lack of meaning and fluidity of time in the dream world.” (Source: Salvador Dalí Museum)

Dalí’s most famous piece is The Persistence of Memory, the painting of the melting clocks. According to the MoMa, Dalí claimed that the “soft watches” had their origin in the remains of a “very strong Camembert” cheese. (Source: MoMa)

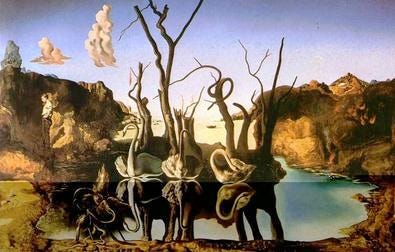

Swans

What’s the connection between Dalí and swans?

Dalí had three pet swans that he later stuffed and displayed at his home (I took a pic above of them when I visited!)

Swans appear in his work Swans Reflecting Elephants and apparently, so does Edward James—one of his greatest benefactors. “James too had his portrait painted by Dalí, appearing as a tiny standing figure in a work entitled Swans Reflecting Elephants, of 1937” (Source: Mary Anderson). Edward James wrote an autobiography of the same name.

Why Now?

According to Tate, the word ‘surrealist’ (suggesting ‘beyond reality’) was coined by the French avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917. (Tate)

As we live more and more online, in a phygital expression of things, surrealism also blurs the lines between what is real and what is dreamed. In our day-to-day, there is a blending of what is real and not, with fake news, deep fakes, CGI-generated marketing. As existential anxieties wage about climate disaster, war, AI, and the future generally, it’s not surprising that people want to go beyond reality.

What Steff Yokta observed in Vogue about Dalí and Schiaparelli is especially poignant: “What’s interesting about looking back on their subversive and surreal work is that these pieces were made in a time when it seemed like the world was ending, a time not unlike our own.”

Widely documented at last year’s Fashion Week, Jess Cartner-Morle wrote in Elle that “The Second Coming of Surrealism is Here”.

Surrealism was born in opposition to the ‘rationalism’ that some artists and thinkers believed had guided Europe into World War I. Surrealists wanted to give the thoughts and ideas of the subconscious, irrational mind their place in culture alongside logic and tradition. It was a visual movement, drawing on the fragmented pictures of dreams and on unconventional depictions of the human body, and soon forged a deep connection with fashion.

Elsa Schiaparelli was a successful fashion designer and Salvador Dalí a young artist when they met in 1930s Paris. ‘Schiap’ gave Dalí access to wealthy benefactors; Dalí gave Schiaparelli an artistic credibility and an edge in her great rivalry with Coco Chanel. Together, Dalí and Schiap became a powerful force in the avant-garde culture of that decade.

So why does it matter if surrealism is having a resurgence in today’s fashion?

If there is even a shred of truth in Miranda Priestly’s Cerulean monologue, then it would make sense that if surrealism influenced fashion last year, then this year it came for art direction, marketing, and then mainstream culture–like weddings.

What is the connection between Scotland, Spain, & Surrealism?

So here is where I insert myself in all of this! If you’ve read this newsletter for some time, you might know that I was living in Spain and now I live in Scotland.

My time living Barcelona was a masters in beauty—and art history. I happened to live on a corner between a surrealist restaurant called Gala, in reference to Salvador Dalí’s wife and muse, and directly across from Gaudi’s Casa Batlló.

Before moving to Scotland, I took a weekend trip up Costa Brava with Gustavo and my parents to visit the beautiful coastal city of Cadaqués, which Dalí called home. My mom and I had to be ripped out of the Dalí museum in Figueres (we were reading every single caption) and the following day, we went on a tour through Dali and Gala’s home in Port Lligat.

Now living in Scotland, I’m shocked to find a surrealist presence here as well. A recent trip up to The Fife Arms (a Hauser & Wirth hotel) surprised me by having a hotel bar named Elsa’s after Elsa Schiaparelli.

According to Studio 104, “Schiaparelli’s love affair with Scotland came from her close friendship with Francis Farquharson, former editor of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines, and wife of the 16th laird Alwyne Compton Farquharson. The notorious couple lived in Braemar castle by the River Dee, where Schiaparelli visited them on many occasion.”

What does this all mean?

It’s possible that all of these surrealist-feeling things are coincidence. I’d like to think that at least some of them are intentional.

All in all, I think it’s interesting to consider the time that birthed surrealism and see that it isn’t so different than the one we’re living in. I return to the quote from Steff Yotka about Dalí and Schiaparelli: “…these pieces were made in a time when it seemed like the world was ending, a time not unlike our own.” Beauty was made through those moments of uncertainty, and too can be made in the world we’re living in.

As for me, I’ve learned that art is everywhere if you look for it.

A fascinating look at some very… interesting… statement pieces. I find the new lobster dresses somewhat disturbing. They make me want to cross my legs and protect my… nether regions. Grin. But a very cool story. Thanks so much.

Lots to love here. Sadly, Frances Farquharson is no relation.